by Jonathan A. Handler, MD, FACEP, FAMIA

I have some opinions about time estimates when doing agile software development using the Scrum methodology. I share them here in case helpful, even though I suspect many will disagree.

Explicit But Hidden Padding

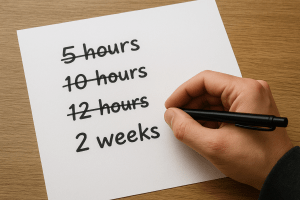

Over the years, I have in the past heard, read of, and seen that people sometimes “pad” (inflate) their estimates when guessing the time required to accomplish a task. People pad for many reasons, which may include:

- They don’t know how long something will take, so they pad to account for the unknown.

- They want to “underpromise and overdeliver” in order to delight their stakeholders.

- They have concerns that there will be negative consequences for failing to meet an estimated timeline.

For Scrum projects, I believe hidden padding should be strongly discouraged. When padding an estimate, I believe the actual estimate and the added padding (if any) should be visibly and separately declared. In addition to a host of other issues, hidden padding can lead to inflated project cost estimates that may cause a good and feasible project to be inappropriately canceled before it even begins, in mid-stream, or even right on the verge of its big success.

Hidden padding can additively propagate, which can devastate projects. For example, imagine developers put padding into an estimate, “just in case,” but don’t visibly note that the estimates have had padding added, or how much. Then the managers, not knowing padding has already been added, add their own padding to the estimates, “just in case.” This cascades and accumulates up the chain of management until a small project looks huge. Until team members have worked with each other enough to guess the magnitude of the hidden paddings, teams may have great difficulty managing projects.

Despite all the padding, and even layers of padding, estimates may still be low. Hidden padding makes it very difficult to get better at the estimating, because if real estimates aren’t routinely required of team members, teams may take longer to learn the skill of better estimation, or may never learn it.

Perhaps most problematically, the hidden padding can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy, or worse. Since the team members have allocated more time for tasks than they think is actually needed, they may delay starting those tasks in order to tackle other requests. Then, if issues do arise with a project’s tasks, the project may get delayed because the padding time for the project task was consumed by other tasks for other projects. Through this mechanism, hidden padding may support inefficient time management and suboptimal task prioritization by team members.

Team members should not have to pad for the unknown, because Scrum has many mechanisms to account for incorrect estimates due to the unknown. I think many would even consider that a key benefit of Scrum. If team members know that they will receive positive reinforcement for accurate estimates, and that they will have no negative consequences for inaccurate ones, then they will have less upside and less avoided downside from adding hidden padding. To avoid hidden padding, project leaders must handle estimates in this way and ensure that every team member knows and trusts that this is how estimates will be handled.

Implicit Padding Via Relative Work Units

Not uncommonly, I’ll ask my wife a question related to time, such as, “how long is the movie we’re going to tonight?” If she thinks the show is long, she’ll tilt her head, give me a funny look, and vigorously nod her head. OK… so now I know she thinks it’s long, but I have no idea what that means to her. Is this a 90-minute documentary that she thinks is “long” because it’s nearly 50% longer than the last documentary we saw? Or are we seeing the full Lord of the Rings Extended Editions trilogy triple feature, totaling a reported run time of 11 hours and 55 minutes (assuming no added intermissions)? It kinda seems like some more specificity is warranted.

The choice of work units in Scrum seems to be a controversial topic, and here is my take: I don’t like relative units (e.g., “points” or “t-shirt sizing”), and seek only to use absolute units like hours (or some other direct measure of time) for estimating time/effort. I have recently read of probabilistic estimates, but I haven’t used them. From what I’ve read I have concerns, but having not actually used them I will not further comment on them right now.

Why don’t I like relative units?

- If the relative units directly correlate to time, then it seems much more straightforward and clearer to just use time instead. There may be some hope that the lack of familiarity among many stakeholders regarding the relative units will lead to less recognition of erroneous estimates, therefore less risk to team members for making wrong estimates. However, I would assert that ensuring incorrect estimates have no negative consequences better addresses that issue.

- Managing the project seems nearly impossible if the units have “wiggle room” implicit in them, are unfamiliar to stakeholders, and/or represent a range (like “3-5 days”). How can you tell if any unexpected issues arose that delayed the effort when 3 days and 5 days of work both fit in the range? If you allow for rounding, then 2.6 days and 5.4 days of work all fit into “3-5 days”. Two tasks, one more than double the effort of the other, would both fall into the same bucket. Knowing when unexpected issues have arisen can have significant utility. For example, it may help identify previously hidden inefficiencies that will affect other tasks, other teams, maybe even other projects. If you knew the estimate was 3 days, but in reality it took 5, you’d have a clue serving as an entry point to a discussion regarding the cause of the difference. If it was because your organization had not licensed a necessary piece of software, and therefore a workaround was needed, you might now choose to license the software and avoid related inefficiencies going forward.

- How can you anticipate how much work will get done in the sprint when everything lives in relative sizing, with ranges having a high end that may be 2x or more of the low end? How can you communicate the current state of the project based on the best available information when the best available information has so little information content? How can anyone expect an executive to interpret a burndown chart that uses units no one understands and whose meaning may even vary by team? I’ve read that burndown charts have fallen out of favor with some folks, but, properly used, I have found them very useful. Of course, burndown charts will more likely be perceived as having little utility if they fail to communicate information anyone can understand because they use unfamiliar, fuzzy, and/or unstable units. I would guess many would regale me with tales of misuse of burndown charts, but I believe I have some tales of my own of their benefits. Used appropriately, I find them helpful, and I haven’t found burndown charts useful when generated from relative work estimates.

- Imagine a software development task could get done in either of two ways. Each leads to an equally good piece of code, but one approach would take 3 days of work and the other would take 5 days of work. Which would be best? All other things being equal, the faster one! If the team estimates work as “t-shirt sizing” where “medium” equates to “3-5 days,” then a developer planning to take the 5-day approach would say “medium.” It would not be immediately obvious to the other developers participating in the estimation process that their colleague was taking a more inefficient approach than the 3-day approach they might have chosen. When the estimations are in hours, it may prove much easier to see when a colleague may be choosing an inefficient path. The process of estimating more finely tends to encourage a little more discussion between team members about the best way to get the tasks done, and I have found that has served our projects well.

In a sense, relative units often create a form of time padding by defining the estimate using a less objective measure than time that allows for “wiggle room”, and/or by using the equivalent of a time range.

Summary

Padding, whether explicitly added by those doing the estimations or implicitly present because of the use of relative work units, often makes managing and improving development difficult or impossible. Therefore, I have found it critical to the success of a project to systematically avoid padding as much as possible. In my experience, that has at least meant following these three approaches:

- Provide positive reinforcement for accurate estimates.

- More importantly, ensure there are no negative consequences for earnestly made but inaccurate ones.

- Ensure work estimates are provided in units of absolute time (and not ranges).

When these have been put in place, they have helped many of my projects, and hopefully others may find success by doing the same.

All opinions expressed here are entirely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinions or positions of their employers (if any), affiliates (if any), or anyone else. The author(s) reserve the right to change his/her/their minds at any time.

Leave a comment