by Jonathan A. Handler, MD, FACEP, FAMIA

Introduction

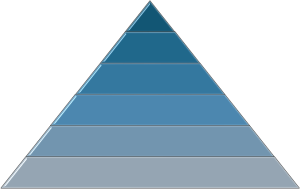

Back in 1943, a seminal work by Dr. Abraham Maslow was published describing the human hierarchy of needs. In this hierarchy, once lower level needs were adequately satisfied (i.e., basic physiologic needs like food and shelter), then higher level needs arise. In other words, people typically don’t urgently feel the need for self-actualization when they lack adequate food, shelter, and personal safety.

It seems likely there is a similar hierarchy in healthcare, a “patient hierarchy of needs.” Based on my prior experiences — as a physician, patient, family member, and friend — I developed a hypothesized hierarchy. As has been said, “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” I’m sure this model is wrong, and I think it’s useful. Validation of the model is warranted, and I may change some or all of it at some point in the future.

The Hierarchy

The hypothesized hierarchy of what the patient seeks, and the health system can provide in return, is shown below:

One might ask, why put “x” level above “y”? For example, I have heard, “I just want my healthcare providers to be nice!” There may be some people for whom that is exactly what was meant. However, I suspect most are starting with an implicit assumption that their provider has no hidden ill-intentions, does not have grossly negligent clinical practices, has reasonable clinical competency, and is available when needed. I think most see these as “table stakes” — qualities they already assumed were present as a bare minimum. For example, I suspect that most people would avoid a doctor who says nice things in order to convince patients to accept therapies that will make the doctor a lot of money but cause serious physical harm to the patient.

The hierarchy does not necessarily attempt to define an ordering of importance. All levels of the hierarchy are important. Rather, the hierarchy aims to identify the pre-requisites for each level, hypothesizing that the next level won’t effectively be achieved in most cases without the layers below being adequately addressed. As in nature, where strong and robust roots enable a plant to flower and flourish, healthcare needs a strong foundation in order for patients to realize their best health. The figure below aims to show this:

Objections

“Delegation” has caused some consternation among those who have reviewed this. There may be a better word, but it relates to a level of trust. It’s not that the patient is obligated to delegate the handling of their care to someone else, rather that the system is such that the patient could comfortably do so if they wished. A key challenge today, as expressed in an earlier post, is that patients frequently shoulder too much of the burden of healthcare. Most people I know don’t want to spend time and energy finding the doctors they need, remembering to schedule tests and appointments, navigating the often choppy waters of insurance, and so much more. But patients can’t delegate the work if that service isn’t offered, and most won’t delegate this work if they can’t trust that the system will make all these decisions strictly in the patients’ best interests, involve the patient in decisions as appropriate, and even send the patients to other health systems when that would lead to the optimal outcome.

Some may question the placement of diagnosis so close to the base of the pyramid. I believe most patients desire a diagnosis because they know it’s a cornerstone of medical care, it often aids in their understanding and sense of control of the situation, and they are (often rightly) concerned that, without a diagnosis, the doctors may be missing something dangerous. There are risks to some diagnostics, and proving the correct diagnosis may not always be the best thing for every patient in every circumstance. That’s why the pyramid qualifies it with “beneficial” diagnosis as the minimum bar and “optimal” diagnosis as the best outcome. If proving the correct diagnosis would lead to greater harm than relying on a provisional one, then the provisional one should prevail as the “beneficial” and likely “optimal” one.

However… I believe that too many clinicians have forgotten the clinical importance of reasonably attempting to make a diagnosis — at least a clinical one — for every issue. Luckily, many patients will improve on their own, but that also means it can be hard to recognize when diagnostic failures have occurred. When patients improve on their own, does that mean no harm occurred? Not necessarily. Some patients improve but never fully recover. I have not seen that completeness of recovery gets assessed for most diseases. So, unless they hear otherwise, it seems as if most clinicians implicitly assume that either the patient fully recovered or a full recovery could not have been achieved. Those who do return to full health might have had their suffering alleviated more quickly if the optimal diagnosis had been made. When we successfully treat without the optimal diagnosis, we are just getting lucky. Some say it’s better to be lucky than good, but our patients need us to be both. Not everyone needs a proven diagnosis, but most expect their doctor to try to make a diagnosis, and to try to make the right one. Too often, that doesn’t seem to happen at all.

I haven’t focused on the lowest level because I believe a big part of our legal, regulatory, and healthcare infrastructure in the United States is designed to assure this level. This level has not been perfectly addressed; however, it seems much better covered than many of the higher levels.

What is the point of this?

The hierarchy is designed as a strategy for healthcare: an ordered sequence for building, evaluating, and optimizing healthcare environments. Too often, what is measured, optimized and done in healthcare is determined by short-term goals: what’s easiest, what’s the hot topic of the day, and what affects payment rather than what’s most important to patient care. This near-sighted, tactical approach practically guarantees that the best patient care will not be realized, because the tactics arise from a different set of goals. “We can save money by saving lives” sounds appealing, but it also makes health a path to an outcome rather than the outcome itself. It also implies a strategy focused only on the subset of healthcare that can be clearly tied to financial outcomes. That’s more a health cost strategy than a health care strategy. Both are important, and both are different. In a zero-sum environment where reimbursement is limited, healthcare needs to move from “We can save money by saving lives” to “We will save money and save lives.”

If healthcare systems don’t provide services that align with patient needs and priorities, then the money spent will be wasted. No matter how inexpensive, ineffective care is virtually never perceived as cost-effective. The hierarchy aims to provide a path to effective care, the first step in cost-effective care.

The hierarchy may help prioritize thinking about the provision, development, and optimization of healthcare. I am not proposing that higher level activity can’t be done at all until levels below have been fully satisfied (Maslow reportedly felt the same about his hierarchy), however I do think the lower levels need greater focus until they reach an objectively-determined level of adequacy.

Metrics are needed that objectively measure performance at each level of the hierarchy for every patient, every time. Without actively measuring the quality of most or all interactions at each level, only guesswork can be used to assess each stage in the hierarchy and guide improvements for a health system overall and for individual cases. This especially holds with regard to the quality of diagnosis and therapy, since they sit near the base of the pyramid. I don’t find it adequate to say “We assume it’s okay because we haven’t heard otherwise,” or “We can’t measure everything, so we’ll measure a few key items.” When discussing measuring the quality of every encounter, it seems the talk inevitably turns to measuring quality only for a few diseases. Performance on a few diseases does not necessarily provide insight on performance in general. As much as reasonably possible, measuring performance at each level of the hierarchy, every time, helps achieve a strong healthcare foundation. I believe this represents a key innovation needed in our healthcare system, as noted in an earlier post (which also proposed metrics aligned with this hierarchy).

Conclusion

To achieve different outcomes in healthcare, the healthcare ecosystem needs to do things differently. If the ecosystem continues to measure, prioritize, and execute tactically rather than strategically, then it will continue to achieve outcomes that fail to align with patient needs and expectations. That seems a waste of time and money for everyone. Too many organizations spend time and resources searching for the increasingly rare “low hanging fruit” that, even when found, won’t substantially change the care for most patients. With any luck, the hierarchy will help guide those in healthcare to nurture their healthcare “soil,” building strong roots that enable patients’ health to blossom.

All opinions expressed here are entirely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinions or positions of their employers (if any), affiliates (if any), or anyone else. The author(s) reserve the right to change his/her/their minds at any time.

Leave a comment